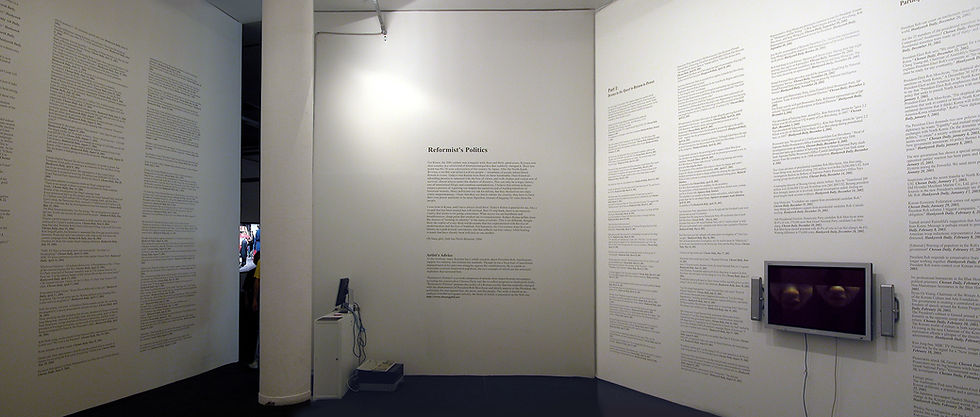

The Politics of Reform, 2004 –Lettered newspaper headlines covering an entire wall.

Maru - Third Conversation

The Politics of Reform – Emotions Pinned to the Wall

Lucy: When I first encountered “The Politics of Reform” (2004), it reminded me of Hans Haacke’s “Shapolsky et al., Real Estate Holdings”. The one that exposed corrupt real estate dealings tied to the Whitney Museum, and got canceled. But your piece felt… quieter. It wasn’t an exposé, but a kind of emotional tremor.

Sangghil: That work was made for the 26th São Paulo Biennale. I covered an entire wall with headlines from Korean newspapers—specifically during the time when President Roh Moo-hyun was impeached. Two sharply opposing media outlets—Chosun Ilbo and Hankyoreh—were spewing politically charged headlines day after day. I didn’t believe either represented the people. To me, they were both manipulating public opinion to serve their own political agendas. Instead of shouting, I decided to paste those voices onto the wall—as if the wall itself were speaking.

Lucy: I remember being struck by that contrast. Some headlines were aggressive, others strangely sentimental. But together, they formed this strange, vibrating field.

Was the political climate already that tense?

Sangghil: The impeachment motion had passed the National Assembly. The entire country was polarized. Every day brought another wave of charged, emotionally-laden articles. I wasn’t trying to make a “statement” about politics. I wanted to trace the emotional turbulence— the atmosphere that media creates.

The Politics of Reform, 2004 –

Lettered newspaper headlines covering an entire wall.

Lucy: So the wall wasn’t just informational—it was emotional topography. I heard there was a whole backstory too?

Sangghil: Yes, a rather absurd one. Around the same time, I was running a private museum and directing a long-term research project called “Re-reading Korean Contemporary Art.” The Korean Culture and Arts Foundation had supported it for four consecutive years. Then suddenly, my proposal was rejected without explanation. When I filed an administrative complaint, a bizarre backlash followed—anonymous personal attacks from committee members, public defamation.

It was as if I had violated some invisible taboo. I requested internal documents and discovered dozens of irregularities in the grant review process. I compiled them into a white paper and sent it directly to the foundation’s director. A few days later, the Secretary General came to me, apologizing profusely and asking me not to release the report publicly.

Lucy: That’s… not just an unfortunate situation. That’s institutional intimidation. And then you were selected for São Paulo right after?

Sangghil: Yes. But once the news broke, the foundation suddenly announced they would cut my international grant to one-sixth. I accepted. Told them I’d fill the exhibition space with newspapers if needed—and I meant it. I even prepared a statement explaining exactly why it was made of paper. They panicked and withdrew the decision. Then, without explanation, they still slashed ₩5 million from the budget. I let it go.

Lucy: The whole process feels like it became… part of the work. Funding, withdrawal, pressure, bureaucratic maneuvering—as if the piece extended beyond the wall.

Sangghil: Even during installation, a curator came and questioned the “political nature” of the piece. I told her: “This installation was formally requested by the Biennale office. Unless I receive an official rejection, please don’t interfere.” Later, I found out President Roh was planning to visit the Biennale during a diplomatic trip. That explained the sudden nervousness.

Lucy: But what’s strange—this was such a striking piece, and yet there were barely any reviews or mentions. Even now, I had never heard of it until recently.

Sangghil: No press, no critics, no curators ever mentioned it. Not once. For over 20 years. I don’t believe it was forgotten. It was deliberately ignored. Avoided.

Lucy: Yes. This feels like collective silence—an institutional instinct to not look. 《The Politics of Reform, 2014》 wasn’t censored. It was… too accurate to be spoken about. It’s one of the few works I’ve seen in Korea that critiques power from within the institution—not by shouting, but by layering affect. Not as protest, but as presence.

Sangghil: Korean society has since witnessed two more impeachments—Park Geun-hye and Yoon Suk-yeol. To me, these events are all part of the same long arc. Power in Korea isn’t held by the people, but split among four major forces: politics, capital, media, and organized labor. They compete, collude, and shift alliances to control the narrative. So this silence around The Politics of Reform—it’s not incidental. It’s because the work hit too close to the bone.

Lucy: Then that wall of headlines wasn’t a moment in 2004. It was the first act of an ongoing drama. And even now, someone is probably preparing another wall, writing out the next wave of slogans—to be posted, and possibly torn down.

Sangghil: In 2017, during the impeachment of President Park, I made a follow-up piece called 《A Certain Democracy, 2017》. This time, I shared it on Facebook and my blog. I was trying to bypass the institutional silencing. But even there—I met another kind of censorship: indifference. No response. Not from the art world, nor the public. It was like we all silently agreed not to speak.

Lucy: That’s perhaps even more disturbing—when the silence becomes social, not just institutional. It’s as if censorship has evolved—from formal suppression to collective indifference. And that indifference becomes a new kind of power.

Sangghil: Yes. And I watch it—like a mirror of silence. Of course, my silence means something very different from the society’s.

A Democracy, 2017

facebook & blog works

This is where the third conversation of MARU ends.

You may now see and hear the fourth conversation—

with a different time, a different body, a different silence and a Position.

Contact: sangghil.art@gmail.com

상길: